Tourism of duty

Dear friends,

While you’re waiting for your baggage in Mexico’s shiny new Felipe Ángeles international airport, the walls promise the train is coming. Shapes and colours catch the eye, anticipating the ride of your life through the rainforests, fauna, Mayan ruins, and blue lagoons of the nation’s southeast, from the Yucatán peninsula to the Campeche jungle to the Caribbean coast.

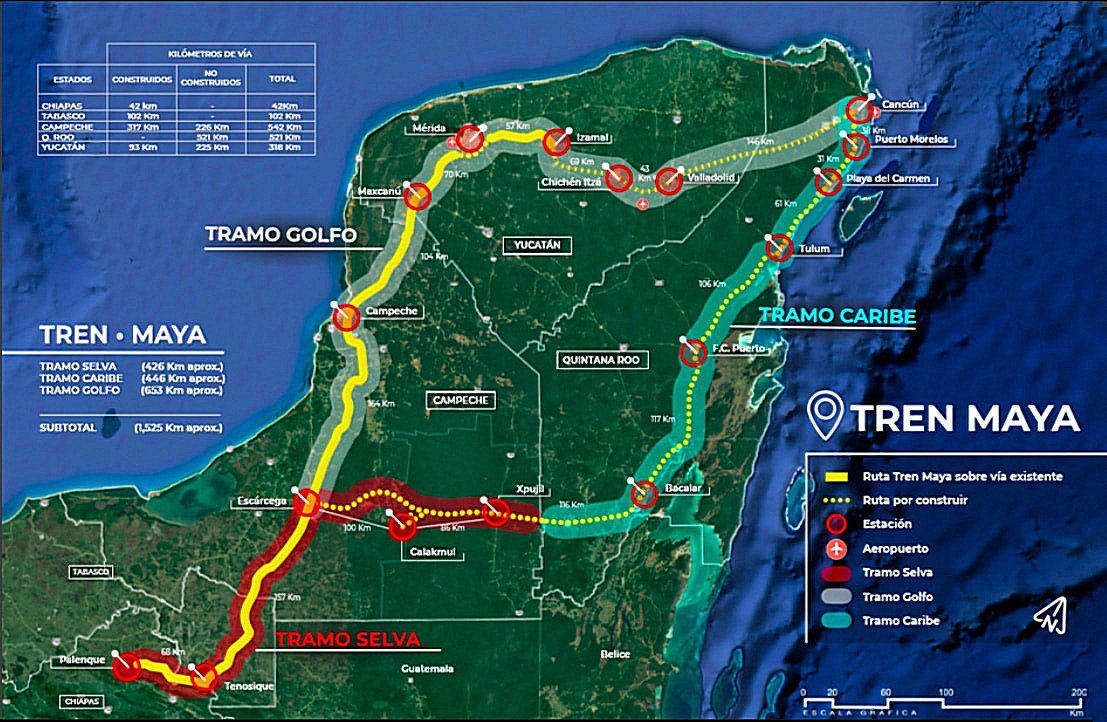

The ads are for the Tren Maya (Maya Train) – the flagship tourism megaproject of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) administration, which is about to enter its final year after López Obrador assumed the presidency in December 2018. Slated for launch in December, AMLO has professed that the Tren will bring new prosperity to the region, whose population is predominantly indigenous Maya. A 2020 UN-HABITAT analysis projected that nearly one million jobs would be created. For the first time, the key sites of the Mexico’s Maya region – the historic city of Mérida, the ruins of Palenque, the Calakmul biosphere, the beach towns of Bacalar and Cancún – will have a continuous transport link for taking tourists on a cultural, historical, gastronomical and ecological odyssey.

As you emerge from baggage collection into the main part of the terminal, the ads for the Tren Maya are joined by the insignia of the Defense Ministry (Sedena - Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional/National Ministry of Defense). Heavily armed and uniformed members of the Army, National Guard and Navy patrol the grounds under screens directing visitors to bus connections to the tourist districts of Centro, Roma and Condesa. Felipe Ángeles is situated on the Santa Lucía military air base in the State of Mexico and run by Sedena, whose subsidiary company also built the airport.

The ads on the military airport walls are not the only link between the Tren Maya and the armed forces. Sedena is also building three of the Tren stations, a tourist information centre, and six hotels on the route. Indeed, they are busy throughout the country building public works and expanding their ranks – constructing another new airport in Tulum and taking charge of customs stations, sea ports, and another significant railway project in the south of the country. The Navy recently assumed control of the Mexico City international airport, while the National Guard - officially transferred from a civilian to a military body last year - exercises increasing local control over everything from migration policy enforcement to subway security. A recent Financial Times report estimates public projects are staffed by at least 350,000 full-time workers from Defense and the Marines, and that annual revenues for the Ministry now fall in the tens of billions of dollars.

The mass militarisation of Mexico under AMLO and his Morena party has been a genuine shock to many. Much of the hope invested in his election in 2018 was a hope for peace – the demilitarisation of ‘war on drugs‘ public security (he promised to ‘send the soldiers back to the barracks’); amnesty and national dialogue on organised crime; investment in social welfare (‘abrazos no balazos’/‘hugs not bullets’*). The results, five years on, bear little resemblance to that vision. A Wikileaks cable from 2006 – 12 years before López Obrador went to the 2018 election pledging peace – shows that, if elected, the President always intended to bolster the power of the military.

Even putting aside obvious democratic and progressive concerns about a militarised society, this is an institution that has real questions to answer in Mexico. The present and historical role of the armed forces in forced disappearance, spying on activists and journalists, and extra-judicial killings is well-known, while their complicity with drug trafficking and other organised crime remains an open question. Their active collusion on the disappearance of the 43 students of the Ayotzinapa teacher's college, a world-famous case which under AMLO was supposed to be a watershed for achieving justice against the actions of previous regimes, is indisputable. And they just got away with it, again. Here is a photo of General Salvador Cienfuegos at the inauguration of the Felipe Ángeles airport in March last year.

If Mexico’s current political leaders, now aggressively seeking the re-election of their chosen successors, were looking for a location-laundering** opportunity to unite any ambitions they might have for authoritarian control and private profit-making, they could not have found a better one in the current boom in tourism and uptick in remote workers and foreign residents, particularly from the neighbouring United States. From January to April 2023 alone, international tourism was worth $10.74 billion to the Mexican economy - 17% more than the same period in 2022 and 17.5% higher than in 2019, as reported by the national statistics agency. Earlier this year Congress agreed to have 80 percent of tourism taxes (for non-resident visitors to Mexico, this is currently 533MXN/32USD per person/visit) flow directly to the Defense Ministry, for the operation of a trust run by Sedena.

Within this, the Tren Maya has also been declared a project protected by national security protocols, preventing public disclosure about its operations - making it much more difficult to ask questions, for example, about the International Rights of Nature Tribunal's judgement that the Mexican state has committed “crimes of ecocide and ethnocide” in the construction and operation of the Tren. Or how the state achieved the mass privatisation of collectively owned land required to build the railway. Or how the Tren intersects with crackdowns on migration to/through Mexico from nations bearing the brunt of the globe's crises.

Pet project, employment generator, ecotourism triumph, ambivalent promise, ecocide, ethnocide. Whatever you make of the Tren Maya right now, it is something to notice that much of Mexico's current big policy, trade and tourism moves are being lashed into place by a structurally unaccountable armed state conglomerate which is directly implicated in continuing abuses. Notwithstanding the high levels of public trust in the armed forces in a country where trust is more often a life or death matter, Mexico's survivors of state violence and its vast civil society remind us that militarising public and citizen security cannot be expected to serve its own people, save perhaps to build a tourist train on time.

Thanks for staying with The Troubled Region,

Ann.

*this is the more common translation, but for mine the better one is Philip Luke Johnson’s ‘hugs not slugs’

**in the absence of a better term for ‘tourist-washing’ - is there one? (cf. greenwashing, pinkwashing...)