Pedro Pascal as foreign policy*

Dear friends,**

In The Last Of Us, Pedro Pascal's Joel Miller must shepherd Ellie, played by Bella Ramsey, across terrain marked by the mass expiry of most of the world's humans. There is danger around every corner. Trust between the remaining mortals is as thin as the spent layer of soil that erupts to release hordes of carnivorous undead in episode 4.

The episodes were dropping early this year while I was reporting on migration in southern Mexico — interviewing migrants from Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela in the border city of Tapachula and talking by phone with people on the road trying to use CBPOne, the smartphone app now required by the US government for asylum applications.

I was convinced to start watching after everyone I knew started recommending episode 3, which is indeed a beautiful work of queer apocalyptic tenderness. I kept going as the series generated a nagging, inchoate resonance with the stories I was hearing from the migrant trail. And as the Instagram algorithm started delivering daily Pedrito content, from which I learned that Pascal himself arrived to the US with his family as a refugee from 1970s Chile. You hear the meaning of this in his SNL monologue: the veteran actor's voice catches as he says "my parents fled Pinochet and brought me and my sister to the US...they were so brave."

The Last Of Us portrays a heart-in-throat journey through an ungiving world; an impossible-odds adventure that seeks its conclusion in human salvation. It does this while the literal experiences of so, so many who are crossing continents right now are rarely portrayed in such a way in politics and culture, if we even hear about them. It was somewhat by chance that I learned of these epic journeys when I first went to Tapachula to report in 2019. I returned this year, meeting more heroes and holy people and ordinary fighters and ambiguous moral actors whose real lives in real time somehow remain outside the bounds of MSM imaginability.

Mexico’s southern border

While it was always a border hub, the city of Tapachula has become an extraordinary site of global encounter in recent years as people on the move from countries in Central and South America, the Caribbean, South Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Eurasia have crossed into Mexico from Guatemala, most with a plan to continue traveling north to enter the US. At least 37,606 have done so in the first three months of this year. Within that number, Mexico’s refugee authority says the ‘top ten’ countries of origin are Haiti, Honduras, Venezuela, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Afghanistan, Brazil, Chile, and Nicaragua. Thousands of the migrants who enter Mexico via the Guatemala land border arrive from South America (often after many years in Chile or Brazil to where they'd flown from their country of origin, such as Haiti, Senegal, or Bangladesh), traveling on foot to Colombia and then Panama via the Darién Gap, which joins South to Central America.

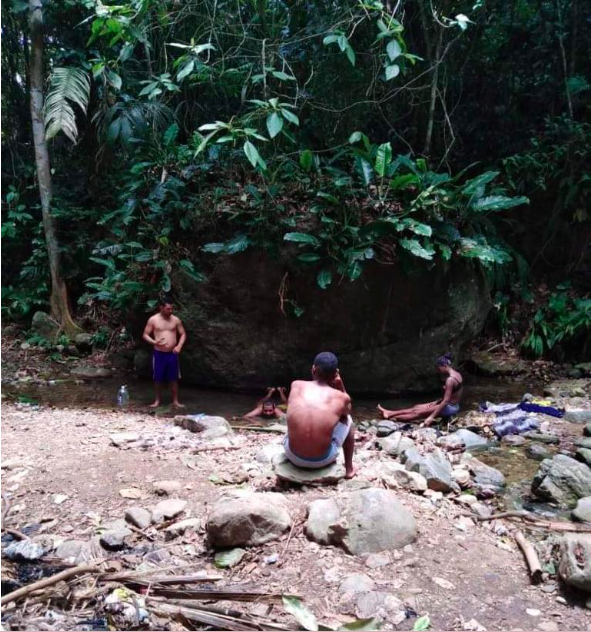

They say the journey through the Gap, a borderland between Colombia and Panama where construction on the Pan-American Highway was halted, is one of the most dangerous migration routes in the world. When I met Jacob in Tapachula in 2019 he sent me the photo below, taken on his phone when he was traveling through the Gap, not sure if he'd make it. When I was back in the city in January this year, an Afghan family told me of hiking through the jungle with a sick toddler and no medicine, brothers taking turns to watch out for danger while the others slept at night. (I lost contact with Jacob and can only hope he is well; I've heard the brothers and their families made it over the US border.***)

Joel and Ellie are the heroes of The Last Of Us: survivors against all odds, snatching moments of laughter and tenderness despite the constant threats to life, each one a new iteration on ruin. Meager rations get stolen, drugs for pain and fever must be traded for batteries, a 'safe' house harbors the flesh-crazed mushroom people, the good guys have factionalised and split. Perhaps especially because the series is based on a video game, the main characters' journey is the stuff of moral dilemma and personal projection as we wonder if we'd join the resistance or rat out our neighbors or let a child die. A certain safety is reached in the final episode, even as blood-soaked Joel lies to groggy Ellie. The sun rises through the mountains, over a winding, well-reinforced road.

The migrants who arrive to Tapachula might only hope for a similar resolution. Those who make it to the US border are routinely deported, sent back to square one from where they try and try again to 'win' the shittiest action-adventure game imaginable. They save for the journey in currencies that barely buy bread, waiting to be able to leave places where armed gangs could come for you any time if food and medicine shortages have not already. They work for coins and sleep with one eye open on rented mattresses. The injured are left behind and adults go without nourishment so that their babies are fed. Rape and kidnapping on the trail is commonplace, as is extortion. Determined people bake in the sun for days on end, stuck waiting for work or permission to move. There's fights and surprises and romance and heartfelt calls home. But instead of survivors of an epic journey through a multiply dangerous world, the stories of the thousands upon thousands who travel to the US border from its peripheries barely register in the news. They are labelled as law-breakers, and stigma keeps doing its work from there. Even when they burn to death in an illegal prison just a stone's throw from reaching the apex of their journey.

Thanks for staying with The Troubled Region,

Ann.

*nb he is already Easter eggs, phonology textbooks, International Dark Sky Places, and Naloxone.

**Welcome to the new The Troubled Region. It is the same newsletter as before, but I have moved the hosting from Substack to Ghost. This should not change how your subscription works in any way, but if you have any trouble, let me know and I'll get onto it ASAP.

I'm really happy to be working with a platform that stands against hate speech. And one where creators keep 100 percent of subscriber fees. Big thanks to Jon Hickman and the rest of the Ghost support team who helped me through the migration to Ghost, and to Luke O'Neil of This is Hell World and Simon McGarr of The Gist for their advice and encouragement. Biggest thanks to ultimate Friend of the Letter Daniel Reeders, who is the kind of supporter that freelance writer dreams are made of.

***If you have a subscription to The Progressive magazine or can buy it from a newsstand, you can read more about them in my story 'Yearning to breathe free' which appears in the current issue.